Introduction

Esophagitis dissecans superficialis (EDS) is a rare, benign disorder of the esophagus characterized by extensive desquamation of the mucosal epithelium. The sloughed mucosa may consolidate and give rise to a tubular structure, referred to as a “cast” of tissue, which may adhere along the esophageal length or be expelled partially or entirely via vomiting.1

EDS is characterized by the presence of disconnected sections of healthy squamous epithelium in the esophagus. This condition may result in a cleavage plane located in the suprabasal squamous layers or between the basal cell layer and the lamina propria.2

EDS is believed to be an autoimmune condition as it is strongly associated with autoimmune bullous dermatoses, such as pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid, which may exhibit similar cleavage planes on histology.3 Case studies suggest that up to 5% of individuals with pemphigus vulgaris may develop this condition.4,5 It is also associated with other autoimmune disorders such as celiac disease.6 Damage to the esophageal mucosa due to exposure to heat, chemicals, or physical trauma may also cause EDS. Some common predisposing traumatic factors include smoking, drinking hot beverages, consuming spicy foods, swallowing large amounts of food quickly, repeated forceful vomiting, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, esophageal sclerotherapy, nasogastric intubation, and the use of certain medications, such as bisphosphonates, ferrous sulfate, and certain immunotherapies.2,7–10 This condition has also been observed in patients with strictures, severe infectious esophagitis, and renal failure. Alternatively, EDS may occur idiopathically without any apparent cause or underlying disease.2,3

The literature reports a broad age range with a slight skew towards the elderly, and an even distribution between sexes. There have also been instances of healthy young adults presenting with dysphagia or odynophagia, and in rare cases, vomiting a membranous cast.2,11 This condition is inherently benign, and can be managed by addressing the underlying cause, such as pemphigus vulgaris or celiac sprue, or avoiding the offending medications.

EDS can be mistaken for another rare disorder known as esophageal parakeratosis, which is characterized by epithelial acanthosis and basal hyperplasia of the esophageal mucosa. Parakeratosis presents as a thickened layer of keratinized mucosa, resembling whitish linear plaques.12 Unlike EDS, parakeratosis is neither associated with vomiting of fleshy columns of tissue, nor with pemphigus vulgaris specifically. Parakeratosis has been linked to head and neck cancers, although the condition itself is not considered precancerous. EDS is also often confused with sloughing esophagitis. Both sloughing esophagitis and EDS involve the shedding of the squamous epithelium, which may or may not be accompanied by inflammation. However, EDS typically does not involve necrosis or the formation of ulcers in the squamous epithelium, as found in sloughing esophagitis.2 Finally, Candida esophagitis can present with diffuse, white plaques throughout the esophagus, but will not present with diffuse mucosal sloughing or vomiting fleshy tissue.

Case Presentation

A 66-year-old female patient with obesity presented with a chief complaint of constant phlegm and acid reflux. The patient reported weight gain and trouble sleeping at night. She complained of waking up in the middle of the night and eating before returning to sleep, only to repeat the same pattern for over a year. She also complained of a nervous stomach and tightening. Three years prior to her initial visit, she had a hiatal hernia repair, which was unsuccessful in relieving her acid reflux. The patient was taking quetiapine 400mg for psychiatric purposes. The patient denied any history of coronary artery disease and was on amlodipine for hypertension. The patient had been diagnosed with laryngopharyngeal reflux and was seeking an answer for her symptoms. She denied experiencing any nausea, fever, chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, vision or hearing changes, bladder or skin changes, palpitations, dizziness, syncope, or any other related symptoms.

The patient was prescribed pantoprazole 40 mg, but it did not provide any significant relief. H2 blockers were then added to her PPI regimen, but there was no significant benefit. Subsequently, glycopyrrolate did not provide relief, and she was switched to omeprazole 40 mg. The patient also reported sinus issues and was coughing up a whitish film, indicating GERD.

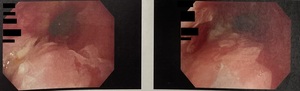

The patient underwent an endoscopy and reflux study. On endoscopy, mildly severe reflux esophagitis with no bleeding and EDS was noted. Tubular casts were observed throughout the esophagus as seen in Figure 1. Additionally, there was erythematous mucosa in the pylorus and erythematous duodenopathy. The reflux study showed no clear signs of reflux. The DeMeester score, a tool measuring esophageal pH, was 6.7, with the normal range being below 14.7.

The pathology report showed that the patient was Helicobacter pylori negative. Distal esophagus biopsy revealed squamous esophageal and cardiac mucosa with mild chronic cardioesophagitis and was negative for intestinal metaplasia. The mid esophageal biopsy showed mid-esophagus squamous esophageal mucosa with sloughing esophagitis indicating EDS.

A course of steroid treatment was attempted in addition to the PPI regimen, but it did not provide symptomatic relief. She had mild improvement with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) therapy. The patient declined immunosuppressive medications or any other further testing as her symptoms were not severe.

Discussion

Esophagitis dissecans superficialis (EDS) is a rare and benign condition that can appear alarming at first glance. Patients may present with symptoms such as coughing up mucosal layers of the esophagus, and endoscopically, it may look like everything is peeling away. However, it is important for clinicians to be knowledgeable about the condition and its presentation to alleviate any fears in their patients.

Research indicates that patients who have several comorbidities may have a higher likelihood of developing EDS. One study has found that as many as 77% of people with EDS take five or more medications, which suggests that EDS may be associated with chronic debilitation.2

Although the etiology of the patient’s condition was most likely idiopathic, she presented with multiple potential predisposing conditions, such as her history of severe reflux that was unresponsive to hiatal hernia repair. Additionally, she was taking psychoactive medications. In recent studies, there has been a potential association between the use of psychoactive agents (particularly SSRIs, SNRIs, or atypical antipsychotics) and EDS. A retrospective study conducted by Mayo Clinic Rochester analyzed data to identify potential EDS cases. Out of 41 patients, 73.1% were on a psychoactive agent. Although the clinical relevance of this association is uncertain, it highlights the importance of considering a patient’s medication history in managing EDS.11,13

The management of EDS depends on the severity of the patient’s symptoms and any underlying risk factors that can be addressed. Fortunately, mucosal sloughing and regurgitation are typically temporary and do not result in lasting complications. The literature indicates that in many cases the condition can be treated by using acid suppression therapy to promote mucosal healing, which prevents further damage rather than addressing the underlying pathophysiology. In addition, discontinuing any medications that may be associated with EDS and addressing any underlying precipitating factors may be beneficial. In cases where there is a high likelihood or a confirmed diagnosis of autoimmune-related causes, the use of immunosuppression remains an important treatment strategy.14,15 Despite various treatments, the patient did not experience significant relief, highlighting the difficulty in managing this condition.

Conclusion

Esophagitis dissecans superficialis is a rare benign diagnosis that may seem frightening at first sight and negatively impact a patient’s quality of life. It is crucial for clinicians to recognize the endoscopic appearance of EDS to avoid misdiagnosis and delays in proper management. Despite its intimidating appearance, EDS is not malignant and should not cause undue alarm in patients once diagnosed. Therefore, it is essential for clinicians to be knowledgeable about EDS to provide their patients with accurate information and alleviate any potential fears.