Introduction

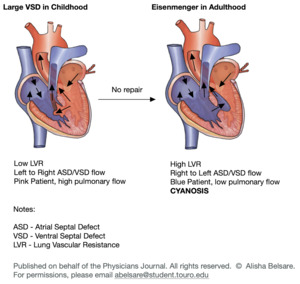

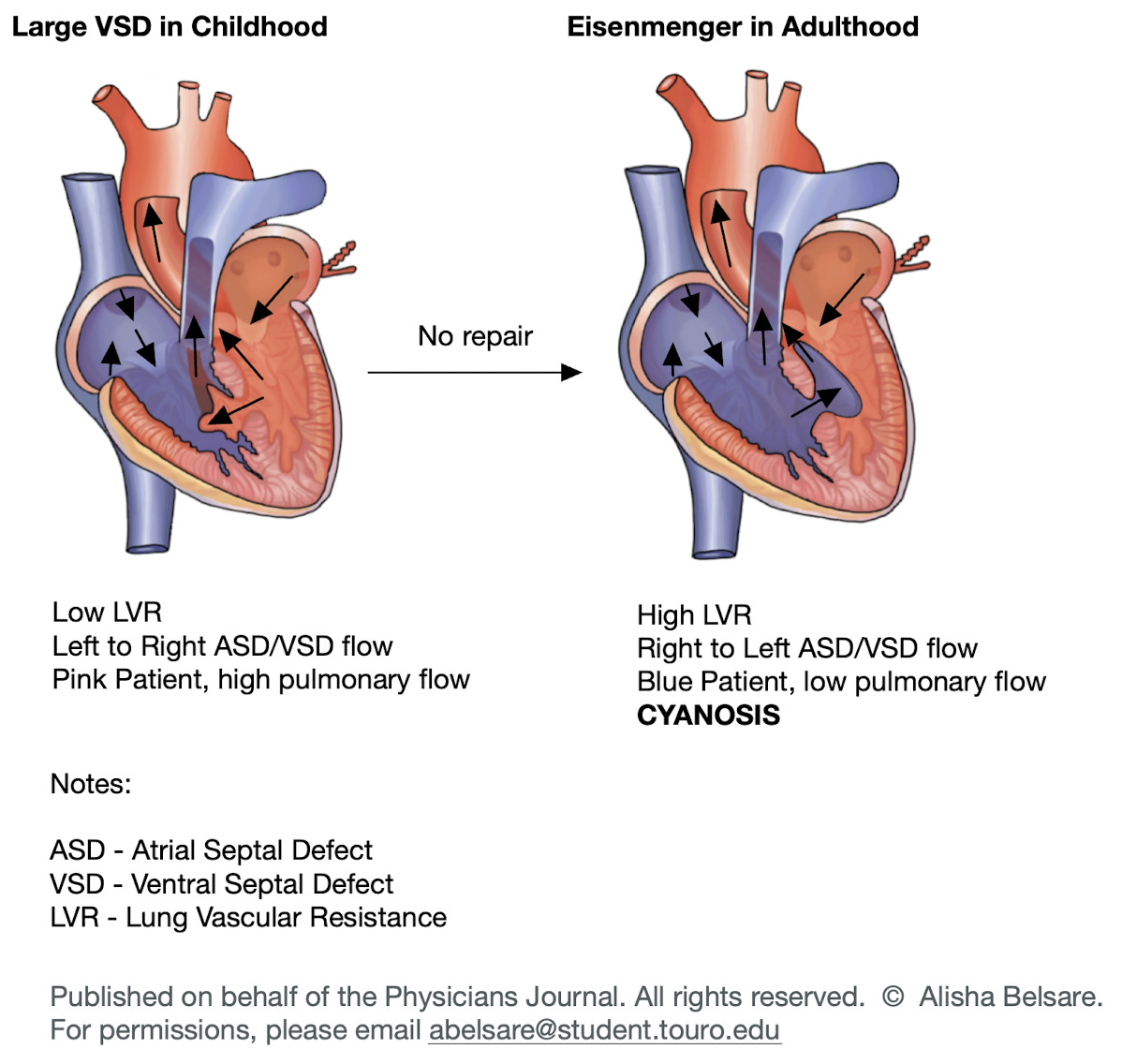

Eisenmenger syndrome is a long-term complication from congenital heart malformations that involves three key defining features: 1) Systemic-to-pulmonary cardiovascular communication (VSD or ASD), 2) Pulmonary arterial disease, and 3) Cyanosis. Due to a ventral septal defect (VSD), the patient presents with a left-to-right shunt. As blood flows from left to right, the patient experiences increased pulmonary artery pressure, leading to elevated pressure in the pulmonary arterial bed within the lungs. This heightened pressure causes endothelial damage and hyperplasia in the lungs. Eventually, as a result of these changes, the pressure on the right side of the heart becomes sufficiently elevated to surpass the pressure on the left side, creating a right-to-left shunt that leads to cyanosis1 (figure 1).

Decades after Eisenmenger initially described this phenomenon, the term “Eisenmenger syndrome” (ES) emerged, incorporating insights from various other medical practitioners. Within this paper, we examine the pivotal figures integral to the establishment of the ES terminology, focusing on their innovative efforts in classifying not only ES but also other congenital heart conditions.1

Eisenmenger

Victor Eisenmenger (Image 1) played a crucial role in advancing our understanding of Eisenmenger Syndrome. Despite the condition being named after him, Dr. Eisenmenger did not originate the term “Eisenmenger Syndrome”; instead, he offered a thorough description of this congenital heart anomaly, eventually leading to its eponymous title. Eisenmenger’s significant insights established the groundwork for grasping complex congenital heart disorders and transformed the field of pediatric cardiology.

Despite health struggles, Eisenmenger proved to accomplish many feats such as revolutionizing the field of cardiology with his discoveries and becoming the personal physician of Archduke Francis Ferdinand.2

Eisenmenger was raised in Vienna and completed his education in the city. He earned his medical degree from the Medical Faculty of the University of Vienna on February 23, 1889. In 1891, he served as an assistant surgeon without compensation at the Surgical Operations Institute under Professor Allerts. In 1894, he joined Professor Leopold von Schrötter at his ENT clinic, where he would make his famous case report.2

In 1897, Eisenmenger wrote an article titled "Die angeborenen Defecte der Kammerscheidewand des Herzens’ in the Germal journal Zeitschr Klin Med. The title can be translated as “The congenital defects of the ventricular septum of the heart”. Eisenmenger detailed the postmortem observations of a cyanotic individual who had passed away at 32 years old, exhibiting a ventricular septal defect and an overriding aorta.3

The article was 28 pages and split into 5 sections. In the first section, he challenged the accepted beliefs on congenital heart disease, presenting an argument against Hunter-Morgagni’s idea that blood flow mechanically caused congenital cardiac defects. Instead, Eisenmenger endorsed Rokitansky’s views, which stated that most forms of congenital heart defects stem from developmental hindrances, particularly abnormalities in the separation of the truncus arteriosus communis. In the second section, he dedicates considerable discourse to the subject of the overriding aorta.3

In the third section, is where he discusses the case of the 32-year-old man. He writes of a 32-year-old man exhibiting clubbing, early childhood cyanosis, moderate dyspnea, and a “buzzing systolic murmur over the apex and a loud second sound.” The patient presented to Eisenmenger’ through a referral from von Schrötter in January of 1894, as he presented with exacerbated dyspnea and peripheral edema. Subsequently readmitted in August due to congestive heart failure, he managed to survive until November 13, when he succumbed to collapse following a significant hemoptysis.3

In the fourth section, Eisenmenger reports the autopsy results and discusses ventricular septal defects, related murmurs, and cyanosis. The subsequent fifth section offers a concise analysis of the potential differential diagnoses.3

During the epoch of Eisenmenger, the common explanation for cyanosis was the overriding aorta. It was reported that the overriding aorta is missing many individuals with Eisenmenger syndrome.4 Eisenmenger disputed that notion and said the increased pulmonary vascular resistance might contribute to the reduction of left-to-right shunting, consequently leading to cyanosis. Eisenmenger failed in the aspect of attributing the actual cause of the cyanosis which is a reversal of the left-to-right shunt to a right-to-left shunt.

In summary, the downfall of Eisenmenger’s interpretation was he regarded enhanced pulmonary vascular resistance as the sole factor responsible for diminishing left-to-right shunting and resulting in cyanosis.

Maude Abbott

Maude Abbott (Image 2) was one of the first female physicians in Canada. She left her mark on medicine as a pioneer in congenital heart anomalies and published over 102 research papers, an enormous feat at that time.5 She was born in 1869 in St. Andrews, a town 40 miles away from Montreal. She was part of the first undergraduate class that accepted women in McGill University. While she wanted to pursue medicine at McGill, the faculty were adamant of not accepting a woman. She was able to attend a medical school affiliated with the University of Bishop’s College. After graduating with numerous honors, she sailed to Europe to learn from medical centers to learn about pathology.

After returning to Montreal in 1897, she began working in the Royal Victoria Hospital and wrote her first paper entitled “On So-Called Functional Heart Murmurs”. In this paper, she assessed 2780 case records, out of which 466 patients had systolic murmurs without any heart disease. This paper highlighted Dr. Maude’s excellence in analyzing large sets of data and drawing meaningful conclusions.5

Her work here led her to being appointed as staff in the Medical Museum in McGill university to catalog the pathological collection. This piqued Dr. William Osler’s interests, who was one of the founding members of John Hopkins university. He insisted that Dr. Maude’s pathological collection should become the heart of medical learning in Montreal. In the next coming decades, Dr. Abbot became a vital figure at this university in teaching and research. Her opus magnum was her publication Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease in which she also described Eisenmenger syndrome.6

In her writings from Atlas of Congenital Heart Disease, Maude describes the issue of a ventral septal defect with dextroposition of the aorta without any pulmonary stenosis or hypoplasia",7 and notes “both these types form a single clinical group, we are still in need of a generic name”.8 She also distinguishes Eisenmenger complex from Tetralogy of Fallot, where pulmonary stenosis is present.9 Prior to this publication, Maude also discussed in her article “The clinical classification of congenital cardiac disease with remarks upon its pathological anatomy, diagnosis and treatment” the classification of Eisenmenger case as “cyanosis, moderate”. Although the true pathophysiology was unknown at the time without the presence of in vivo right heart catheterization, Maude believed in the aortic origin of the cyanosis.9 With these descriptions, Maude used the terminology “Eisenmenger complex” to report this unusual combination. This term quickly became associated with the described physiologic deviations that arose from the defect.10

Paul Wood

Paul Hamilton Wood (Image 3)was a world-renowned cardiologist, who became one of the leading figures in medicine during the early 20th century. Although Dr. Wood was born in Coonor, Tamil Nadu, India, he lived in various countries over his long career as a physician. He began his medical studies at Trinity College, University of Melbourne, where he graduated with his degree in medicine and surgery. From there, he went on to complete his internship in Christchurch, New Zealand, and decided to move to the United Kingdom with the goal in mind to specialize in cardiology. Upon completing his studies, Dr. Wood taught cardiology at the Royal School of Postgraduate Medicine and Hammersmith Hospital for several years prior to joining the British Royal Army Medical Corps in the advent of World War 2.6

After the war, he returned to Hammersmith and was appointed Dean and Director of the Institute and of the National Heart Hospital, and Physician-in-Charge of the Department of Cardiology at Royal Brompton Hospital. His new role offered him a vast wealth of knowledge and experience in cardiology, which he drew upon to write the first edition of his textbook, “Diseases of the Heart and Circulation” in 1950. This edition and its subsequent publications contained information from over 1000 of Dr. Wood’s clinical cases and was translated into many languages.6

Throughout his studies, Dr. Wood expanded upon Dr. Eisenmenger’s work and later coined the term “Eisenmenger Syndrome”. Wood began by looking at various other heart conditions currently known as Eisenmengers group and compared them to Eisenmengers findings. He looked at conditions such as transposition of great vessels, persistent truncus arteriosus, etc.

He found that in the transposition of great vessels, most cases resembled Eisenmenger’s findings. Specifically, there was a higher oxygen saturation in the pulmonary artery compared to the aorta and right ventricle.4 Wood used a dye-dilution curve to better understand Eisenmenger syndrome. He found that to identify the site of the reversed shunt, it was best to inject a dye into the pulmonary artery, then the right ventricle, and lastly the SVC. A double hump was found in the tracings which occurs when the dye is proximal to the shunt proving the reversed shunt to be at an atrial level.4

Wood found that the most common cause of death from Eisenmenger syndrome was Haemoptysis. There were many theories as to why such as pulmonary infarction from arterial thrombosis, rupture from a thin-walled arteriole, or a rupture of an aneurysm of the pulmonary artery.4

It was shown through experiments that acetylcholine injected directly into the pulmonary artery at a dose of 0.5 to 1.5 mg, is an ideal vasodilator. This is because this quantity is inactivated by cholinesterase by the time it reaches systemic circulation.4 Lowering the pulmonary artery pressure and resistance, and increasing cardiac output, helped cases of Eisenmenger syndrome.

Wood found stenosis of the right pulmonary artery by its origin to have protective effects in Eisenmenger syndrome. He found functional and anatomical evidence that when the origin of the pulmonary artery is atresic in Eisenmenger syndrome, its distal branches and muscular arteries are normal. These branches and arteries were not subject to high pressure but vessels on the other side had all the features of Eisenmenger syndrome.4 These findings showed that stenosis can decrease pulmonary pressure.

In conclusion, Eisenmenger syndrome started to become known as pulmonary hypertension causing a reversed shunt and cyanosis, mainly at an atrial level. This was because of Wood’s findings which saw that many diseases such as ASD, VSD, persistent truncus arteriosus, transposition of great vessels, etc, can cause Eisenmenger syndrome. The thing these conditions had in common was a large communication between two circulations causing an increase in pulmonary artery pressure and resistance. He found by decreasing this resistance, either through medications such as acetylcholine or by stenosis, patients with Eisenmenger syndrome improved.4

Modern day guidelines in the treatment of Eisenmenger syndrome

Surgical intervention for Eisenmenger syndrome aims to alleviate the underlying anatomical abnormalities contributing to pulmonary hypertension and right-to-left shunting. Depending on the specific cardiac anatomy and patient’s clinical status, several surgical procedures may be considered. These interventions often involve addressing the underlying cardiac defects, such as closure of septal defects (VSDs or ASDs) to eliminate the shunt, pulmonary artery banding to reduce pulmonary blood flow, or creating systemic-to-pulmonary shunts to optimize blood flow to the lungs.11 Surgical correction might be feasible for specific patients with Eisenmenger syndrome if there exists a notable level of blood flow from the left to the right side of the heart and if the pulmonary blood vessels demonstrate a positive response to medications that widen them.12 The criteria determining suitability for surgery are not uniformly established and might involve assessing factors like how effectively the pulmonary arteries can dilate and whether the ratio of blood flow from the lungs to that from the body is at least 1.5 to 1.0.13 In select cases, advanced procedures like heart-lung transplantation may be considered for definitive management. Flexible bronchoscopy was routinely performed to evaluate the condition of the donor airways and remove any retained secretions. Following sternotomy and opening of the pleural cavities, adjustments were made to the ventilation to prevent lung collapse and ensure full expansion.14 Lung preservation involved using a single-flush technique with cold blood perfusate, along with prior infusion of prostacyclin directly into the pulmonary artery. During tracheal stapling, the lungs were inflated adequately to verify complete expansion and prevent residual collapse.14 The choice of surgical procedure depends on various factors, including the patient’s age, overall health, cardiac anatomy, and severity of pulmonary hypertension.