Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, a novel coronavirus first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, has sparked a global pandemic that has profoundly altered public health and social dynamics worldwide. This enveloped virus, part of the coronavirus family, primarily spreads through respiratory droplets and has shown the capacity to mutate, giving rise to various variants that can evade immunity from previous infections or vaccinations. As of early 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports over 770 million confirmed cases globally, with nearly 7 million fatalities, underscoring the ongoing challenge of managing COVID-19 and its variants.1

The clinical manifestations of COVID-19 extend beyond the respiratory system, impacting multiple organ systems and leading to a range of complications, including cardiovascular, neurological, and gastrointestinal issues. Notably, COVID-19 has also been linked to various dermatologic manifestations, which can serve as critical indicators of the disease, with skin manifestations observed in up to 20.4% of cases, commonly affecting the trunk and limbs.2 Another meta-analysis confirmed this, finding skin manifestations in 29% of patients who tested positive for COVID-19, with symptoms lasting a mean of 7 to 9 days. The most frequently affected areas included the feet and hands (75%) and the trunk (71%), suggesting significant dermatological implications.3

COVID-19-related cutaneous manifestations encompass a range of presentations, including pernio-like lesions (commonly known as ‘COVID toes’), maculopapular rashes, urticarial eruptions, vesicular lesions, livedo reticularis, and petechial and purpuric lesions. These skin symptoms, which may appear alongside or even before respiratory signs, are thought to reflect the immune system’s response to the virus and can vary based on the patient’s health and demographic characteristics. Recognizing these cutaneous indicators is crucial for dermatologists and clinicians, as they may aid in the early diagnosis and management of COVID-19, potentially improving patient outcomes.

The objective of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the dermatologic manifestations associated with COVID-19. By detailing these findings, the paper aims to equip healthcare professionals with essential insights for early recognition and management of skin-related COVID-19 presentations, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and supporting the multidisciplinary approach necessary to combat this pervasive disease.

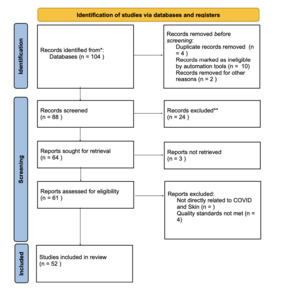

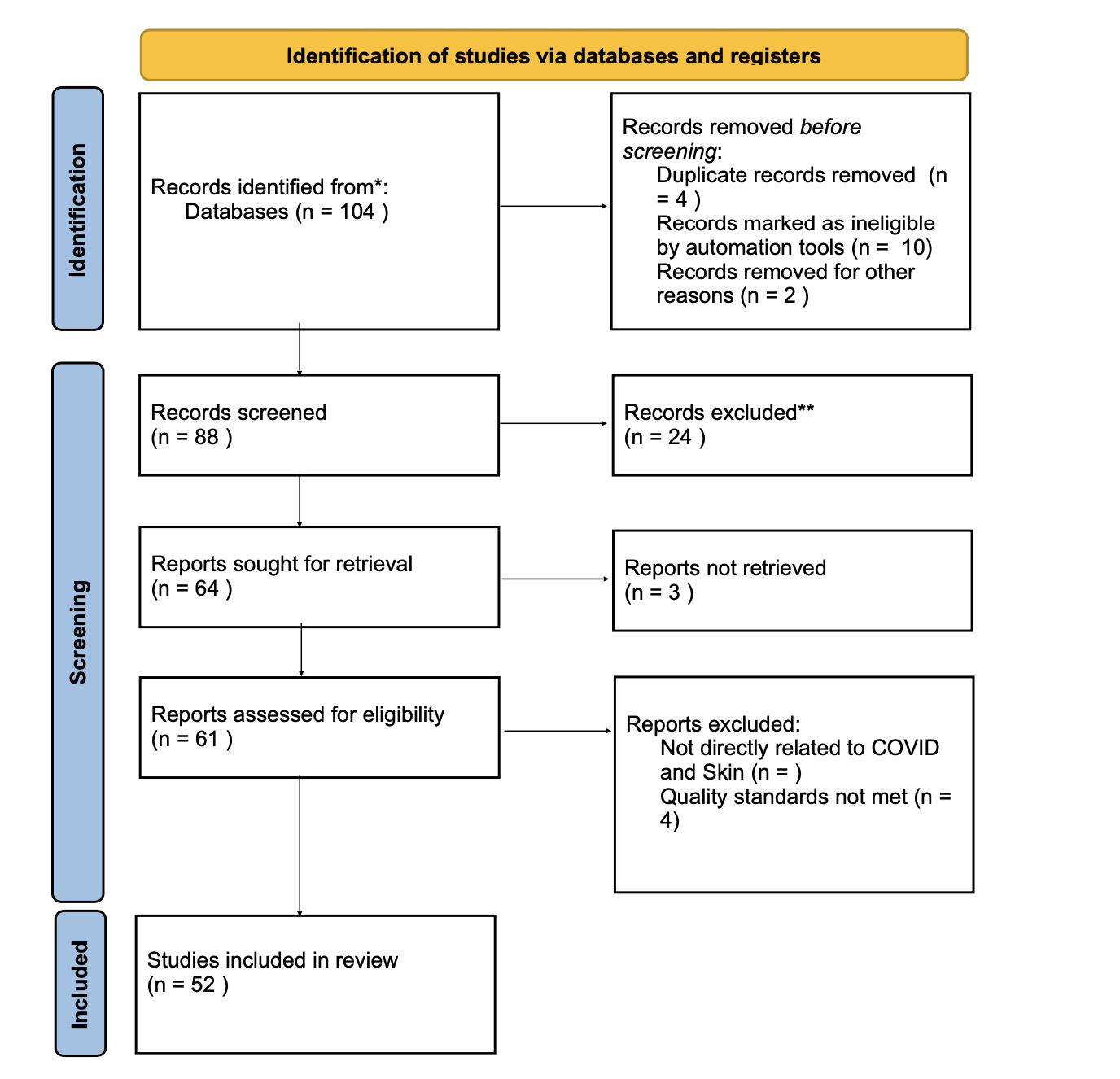

Methodology

Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using major scientific databases, including PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, and Web of Science, to identify relevant studies examining the dermatological manifestations of COVID-19. Search terms included combinations of “COVID-19,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “dermatological manifestations,” “cutaneous lesions,” “skin involvement,” “COVID toes,” “maculopapular rash,” “urticaria,” “vesicular eruptions,” “livedo reticularis,” and “vascular lesions.” Studies published between 2015 and 2024 were included to ensure a thorough and up-to-date understanding of COVID-19-related dermatologic manifestations. This review prioritized studies utilizing case reports, case series, cohort studies, and systematic reviews to assess the various skin-related presentations associated with COVID-19 infection.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

-

Inclusion Criteria:

-

Study Design: Case reports, case series, cohort studies, and systematic reviews focusing on COVID-19-related skin manifestations.

-

Focus on Dermatologic Conditions: Studies addressing specific COVID-19-related dermatological presentations, such as COVID toes, maculopapular rashes, urticarial lesions, vesicular eruptions, and vascular lesions, were included.

-

Outcome Measures: Studies reporting outcomes related to diagnostic value, clinical relevance, or association with COVID-19 disease severity.

-

Language and Accessibility: Only English-language studies accessible in full text were prioritized for accurate data extraction and analysis.

-

-

Exclusion Criteria:

-

Lack of Specific Outcome Measures: Studies lacking measurable outcomes pertinent to dermatological involvement in COVID-19 were excluded.

-

Low-Quality Studies: Studies with inadequate controls, small sample sizes, or poorly described methodologies were excluded to ensure high-quality findings in this review.

-

Experimental Models

-

Case Reports and Series: These studies were included to highlight specific skin manifestations observed in COVID-19 patients, documenting detailed descriptions of lesion morphology, location, and progression.

-

Cohort Studies and Systematic Reviews: Larger studies and reviews were prioritized to examine trends in dermatological symptoms across patient populations, including potential correlations with disease severity, patient demographics, and prognosis.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data extraction from each study emphasized quantifiable findings, such as prevalence rates of dermatological symptoms, correlation with disease severity, and time to resolution of skin lesions. Attention was given to synthesizing data on lesion types (e.g., maculopapular rashes vs. vascular lesions) and their diagnostic and prognostic value. Comparative analyses were conducted to assess patterns in dermatologic presentations across different patient demographics and disease severities.

Limitations and Quality Assessment

Each study was assessed for methodological quality, with criteria including sample size, control measures, and data reliability. Variability in dermatological presentations and terminology across studies was noted, as some lesions, such as COVID toes and vascular lesions, displayed overlap with non-COVID-19 dermatologic conditions. To address these limitations, this review considered only well-documented cases with clear diagnostic criteria, aiming to ensure consistency in findings and enhance the clinical applicability of results.

Below is Table 3, which presents a summary of COVID-19 and its Dermatologological effects. This will be used to reference information on figures

Results

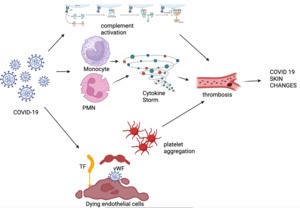

Pathophysiology of Skin Involvement in COVID-19

The Pathophysiology of COVID-19 beings with its envelope. COVID-19 possesses a viral envelope coated with spike (S) glycoproteins, envelope (E) proteins, and membrane (M) proteins, with the S protein playing a key role in host cell binding and entry. The S1 subunit of the S protein contains a binding domain that interacts with the peptidase domain of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) on host cells. In SARS-CoV-2, the S2 subunit is highly conserved, suggesting it may serve as a potential target for antiviral therapies. Upon binding to ACE2, the virus synergizes with the host’s transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2), a cell surface protein expressed on airway epithelial and vascular endothelial cells. This interaction facilitates membrane fusion and the release of the viral genome into the host cytoplasm.9

COVID-19 can cause various skin manifestations, such as chilblain- or pernio-like lesions, which typically do not require specific treatment; however, topical corticosteroids may be used to alleviate discomfort. In contrast, more serious skin conditions, such as erythema multiforme and acro-ischemic manifestations, require treatment with systemic steroids.10 Certain skin changes in COVID-19 patients can also be indicative of COVID-19-associated cytokine storm syndrome (CSS). CSS can be triggered by autoimmune diseases, bacterial infections, viral infections, and other factors, and is characterized by an excessive immune response that results in organ damage due to hyperinflammation. This inflammation is primarily mediated by natural killer (NK) cells and CD8 T-cell cytotoxicity. Continuous activation of proliferation signals and large secretions of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) consistently activate macrophages, leading to increased release of cytokines and chemokines, which drive an unchecked inflammatory response.11 Immunodeficient patients, such as those with HIV or chronic hepatitis B/C, are at a higher risk for CSS due to their chronic pro-inflammatory state, which lowers the threshold for triggering a cytokine storm.

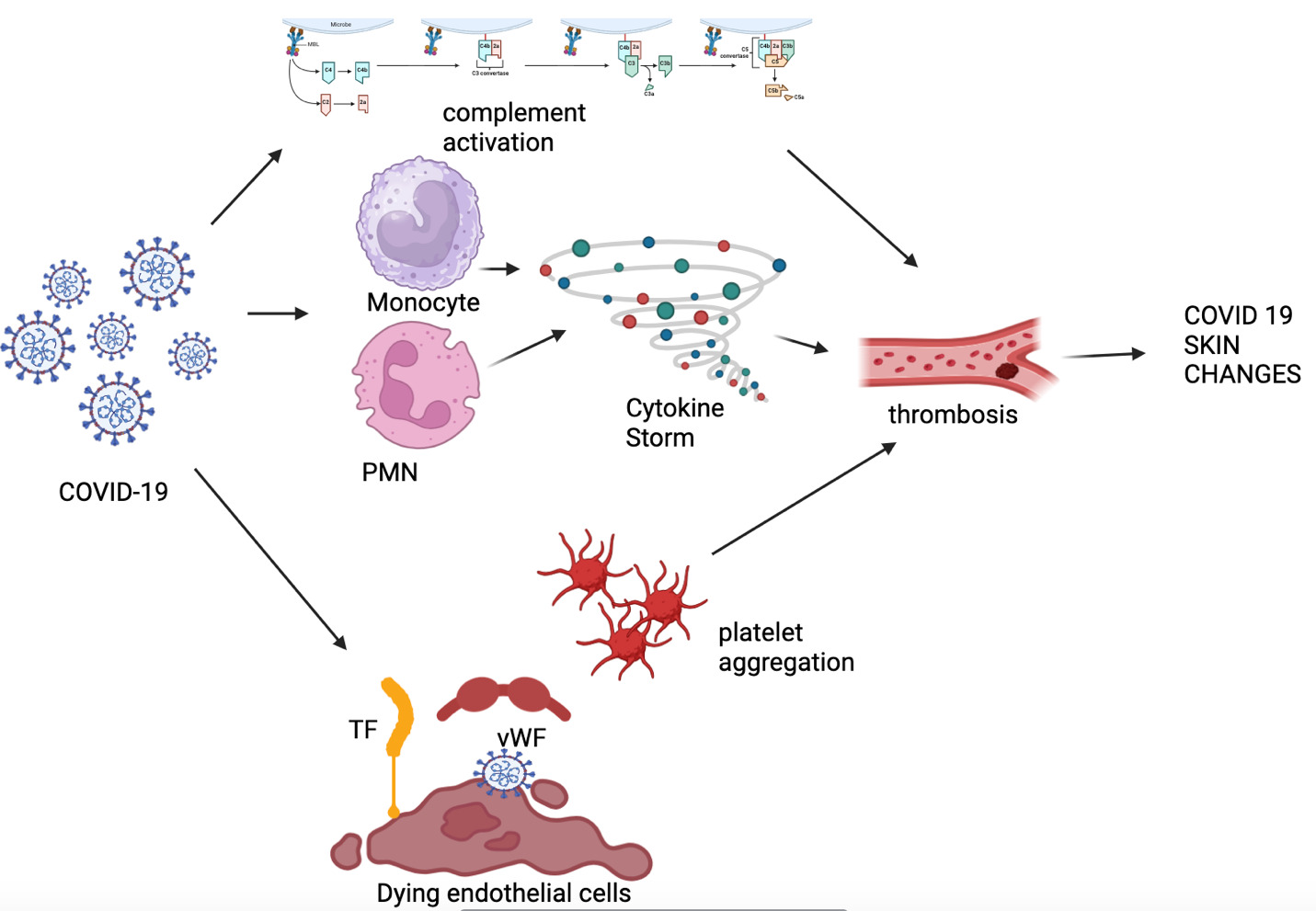

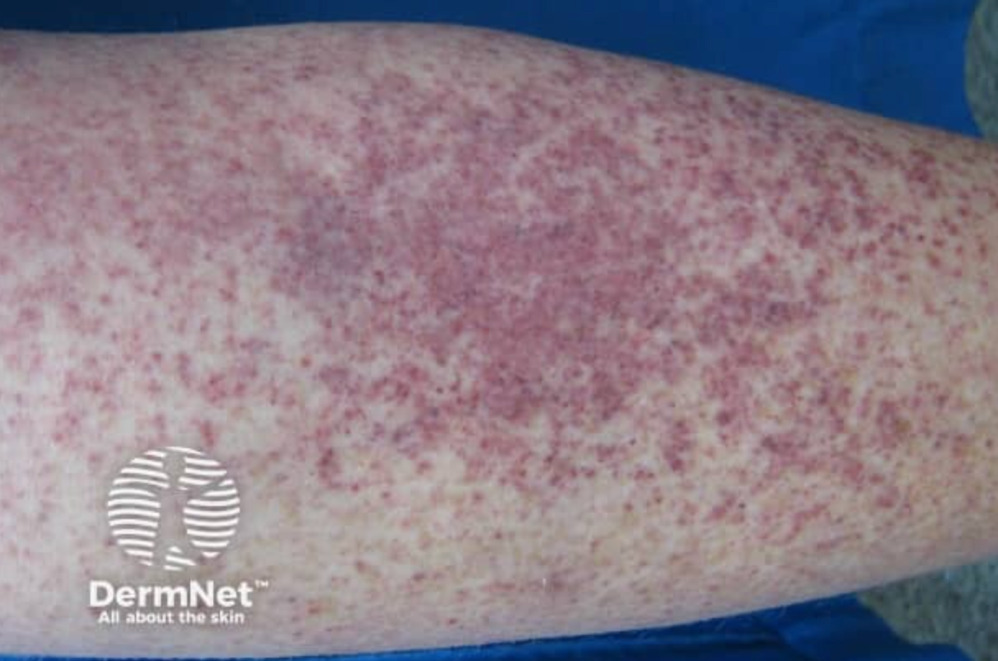

These systemic inflammatory response syndromes can also lead to hematological changes in patients, including increased D-dimer (DD), prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), and prothrombin time (PT). Approximately 71.4% of COVID-19 fatalities were associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) syndrome.12 The increase in inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, induces the expression of tissue factor in macrophages, initiating coagulation activation and thrombin formation. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) and IL-1 act as major mediators in the inhibition of endogenous coagulation. Additionally, COVID-19 infection triggers an acute procoagulant response, leading to elevated levels of Factor VIII, von Willebrand factor, and fibrinogen, which are associated with an increased risk of thrombosis.12 Physicians should be aware of specific skin changes that may indicate an underlying hypercoagulable state, such as livedo racemosa, which represents partial occlusion of cutaneous blood vessels, and retiform purpura, which represents complete occlusion of cutaneous blood vessels.4,13 This is exemplified by the figure 2 below.

Skin changes may not always be directly associated with COVID-19 but could instead be reactions to the drugs administered. Corticosteroids, commonly used to reduce inflammation associated with the virus, can lead to skin changes such as epidermal atrophy due to impaired wound healing. Additional cutaneous changes that can occur include erythema, acneiform eruptions, and striae. The longer a patient is treated with corticosteroids, the greater the likelihood of these adverse reactions.14

To prevent thrombotic events, heparin is used as prophylaxis in patients; however, the most important adverse cutaneous side effect to be aware of is heparin-induced skin necrosis. Lopinavir/ritonavir, initially approved to treat HIV infections and also used to treat SARS-CoV-1, is being investigated for use in COVID-19. Side effects associated with this drug include a maculopapular pruritic rash and, in some cases, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), which can lead to serious multiorgan toxicity.15

Dermatological Manifestations of COVID-19

COVID Toes (Pernio-like Lesions)

Description of Lesion

COVID toes, or pernio-like lesions, present as erythematous to violaceous discolorations primarily on the toes and sometimes on the fingers, recognized as a distinct dermatological manifestation in COVID-19 patients.16 These lesions may appear papular or vesicular, with localized swelling and occasionally desquamation during healing.17 Common symptoms include pain, pruritus, and a burning sensation, although the lesions are generally self-limiting and resolve within a few weeks, sometimes leaving residual hyperpigmentation.18,19 COVID toes are more frequently observed in younger individuals with mild COVID-19 symptoms or asymptomatic cases.16 The image below is an example and is in compliance with DermNet NZ watermark image license terms.

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism behind COVID toes remains under investigation, but immune-mediated processes, rather than direct viral infection, seem central to their development.17 A strong Type I interferon response may drive these lesions by causing localized microvascular inflammation and endothelial cell damage, leading to the characteristic discoloration seen in COVID toes.19 SARS-CoV-2 binding to ACE2 receptors on vascular endothelial cells might also contribute to endothelial dysfunction and microthrombosis, similar to mechanisms seen in systemic COVID-19 complications.20 Additionally, the inflammatory response may elevate cytokine levels, resulting in capillary damage and vascular injury in the extremities.21 Although thought to be immune-driven, some studies suggest the role of direct viral involvement remains uncertain, given the virus’s affinity for vascular and cutaneous tissues.17

Prevalence

The prevalence of COVID toes varies across studies, with estimates ranging from 0.5% to 5.6%, influenced by patient demographics and geographic location.18 European studies tend to report higher rates of pernio-like lesions compared to Asian studies, suggesting potential genetic or environmental influences.16 COVID toes are more commonly observed in younger patients with mild or asymptomatic cases, supporting the notion that a strong immune response in less severe infections may be associated with their development.19

Clinical Significance

COVID toes are clinically significant as a potential early or isolated indicator of COVID-19 in patients who are otherwise asymptomatic or have mild symptoms.16 These lesions may prompt healthcare providers to test for SARS-CoV-2 in individuals who might otherwise go undiagnosed.17 Although generally benign, COVID toes can indicate a robust immune response, potentially suggesting a favorable prognosis.20 From a public health perspective, early identification of these lesions enables timely isolation, which may aid in virus containment.21

Maculopapular Rash in COVID-19

Description of Lesion

Maculopapular rashes are among the most common cutaneous manifestations observed in COVID-19, presenting as erythematous, raised lesions that combine macules and papules. These rashes most frequently affect the trunk, extending to the extremities, and often exhibit a symmetrical pattern.22 The lesions are typically pruritic and blanch upon pressure, which can help differentiate them from other COVID-19-associated rashes.23 The maculopapular rash usually appears several days after the onset of systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, and cough, although in specific cases, it has presented simultaneously with systemic symptoms.24 The rash generally resolves within 8 to 11 days without residual scarring or pigment changes.25 The image below is an example and is in compliance with DermNet NZ watermark image license terms.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiological mechanisms leading to maculopapular rashes in COVID-19 are still under investigation, though several theories suggest an immune-mediated origin. A primary hypothesis is that these lesions are triggered by immune overactivation, specifically through a cytokine storm in which pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6 and TNF-alpha contribute to localized skin inflammation.23 Additionally, ACE2 receptors, which SARS-CoV-2 uses to enter cells, are present in keratinocytes and dermal endothelial cells, potentially making the skin a direct or indirect target for the virus and leading to maculopapular rash development.19 Drug reactions are another possible cause, especially since COVID-19 patients often receive multiple medications that may lead to drug-induced eruptions resembling maculopapular rashes.26 Immune complex deposition in small dermal vessels, complement activation, and secondary inflammation are also proposed to contribute to rash formation, as observed in biopsies of COVID-related skin lesions.27

Prevalence

The prevalence of maculopapular rashes in COVID-19 patients varies widely across studies, with estimates ranging from 5% to 47% of patients presenting with this manifestation.25 In a European study, maculopapular lesions accounted for nearly half of all reported skin manifestations, while lower rates were noted in studies conducted in Asia.24 Middle-aged and elderly patients show a higher prevalence of these rashes, with a slight female predominance reported in some cohorts.23 Regional differences in prevalence may stem from genetic, environmental, or healthcare-related factors, such as the availability of dermatological evaluations and differences in therapeutic regimens.24

Clinical Significance

Maculopapular rashes in COVID-19 patients hold clinical importance, as they can aid in identifying infection in patients who may not yet have been diagnosed, particularly those with mild respiratory symptoms.22 Although generally associated with a moderate disease course, the presence of these rashes has been linked to increased disease severity in some studies, particularly in patients with extensive lesions or concurrent systemic symptoms.25 Recognizing maculopapular rashes as a potential indicator of COVID-19 can prompt earlier diagnostic testing, facilitating timely intervention and isolation to prevent virus spread, especially in resource-limited settings.27 Additionally, the disappearance of these rashes often correlates with clinical recovery, making them a potentially valuable prognostic marker for patient improvement.23

Urticarial Rash in COVID-19

Description of Lesion

Urticarial rashes in COVID-19 patients typically present as erythematous, raised wheals that may appear anywhere on the body, most commonly affecting the trunk and limbs.28 These lesions are often intensely pruritic and exhibit a migratory nature, with individual lesions persisting for less than 24 hours before resolving and reappearing in different locations.25 Generally, urticarial lesions in COVID-19 resolve within a few days without treatment, though some cases may require antihistamines to manage symptoms.29 Additionally, urticarial rashes may manifest as an initial symptom of COVID-19 or later in the disease course, with some reports indicating that they can emerge alongside systemic symptoms such as fever and cough.30 The image below is an example and is in compliance with DermNet NZ watermark image license terms.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology behind urticarial rashes in COVID-19 is believed to be immune-mediated, potentially linked to the cytokine storm seen in severe cases. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-alpha, may stimulate immune cells in the skin, resulting in localized swelling and wheal formation.30,31 Another mechanism may involve the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 receptors, which are expressed in skin cells and blood vessels, potentially causing changes in vascular permeability and contributing to the urticarial response.32 Additionally, the rashes may arise from a hypersensitivity reaction to drugs administered for COVID-19 treatment, complicating the differentiation between drug-induced and virus-induced urticaria.30

Prevalence

Reports on the prevalence of urticarial rashes in COVID-19 patients vary, with estimates ranging from 1% to 15%, depending on the population studied and regional differences.25,30 Urticarial lesions are generally more common in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19, with one study indicating a higher prevalence in middle-aged adults.28 Geographic variability may be influenced by differences in immune response, drug regimens used for COVID-19 management, and demographic factors.29 For example, a Jordanian study found that urticarial rashes comprised a significant portion of the reactive erythema category, highlighting their relative frequency among hospitalized patients.31

Clinical Significance

Clinically, urticarial rashes in COVID-19 patients can serve as early indicators of infection, especially in cases where respiratory symptoms are absent or mild.28 Recognizing urticarial rashes as potential COVID-19 markers may lead to earlier testing and isolation, helping to prevent further virus transmission.30 While typically self-limiting and benign, the presence of urticarial rashes in COVID-19 patients with severe systemic symptoms may suggest an intense immune response and cytokine release, potentially indicating a more severe disease course.25 Consequently, these rashes could provide insights into disease progression, though further research is needed to fully understand their prognostic value.29

Vesicular Eruptions in COVID-19

Description of Lesion

Vesicular eruptions in COVID-19 patients typically present as small, clear vesicles resembling varicella (chickenpox) lesions. They most commonly appear on the trunk but can also affect the face and extremities in some cases.33 These lesions are generally clustered and may be pruritic or painful. The vesicles evolve over 7 to 10 days, often forming crusts before resolving.34 Unlike some other COVID-19-related skin manifestations, vesicular eruptions are frequently reported early in the disease course and may serve as an initial indicator of SARS-CoV-2 infection.35 The image below is an example and is in compliance with DermNet NZ watermark image license terms.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of vesicular eruptions in COVID-19 is not fully understood, but it is hypothesized to involve either direct viral activity within skin cells or immune-mediated mechanisms. The presence of ACE2 receptors in the skin allows SARS-CoV-2 to bind and enter keratinocytes, potentially leading to localized infection and inflammation.34 Another hypothesis involves a hyperactive immune response, particularly the activation of cytokines and complement, which may contribute to vesicle formation and microvascular damage.35 In severe cases, an accompanying systemic inflammatory response, including a cytokine storm, could exacerbate these skin findings and lead to more extensive eruptions.20 Additionally, vesicular eruptions may result from drug reactions, as many COVID-19 patients are treated with multiple medications.36

Prevalence

The prevalence of vesicular eruptions among COVID-19 patients varies widely across studies, with estimates ranging from 2% to 13%, depending on the population and geographic region.20,34 In a study conducted at a Chinese university hospital, vesicular eruptions were observed in 2.5% of COVID-19 cases, often in middle-aged and elderly patients with moderate to severe disease.36 Regional variations in prevalence are likely influenced by genetic, environmental, and healthcare factors, as well as differences in immune response across populations.35

Clinical Significance

Vesicular eruptions in COVID-19 patients can be clinically significant, as their early appearance may help identify infection before more typical systemic symptoms arise.34 Recognizing these lesions can prompt earlier testing and potentially improve isolation measures in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients, thereby reducing transmission risk.35 Although vesicular eruptions are usually self-limiting, their presence in patients with other severe symptoms may indicate a heightened inflammatory response, potentially correlating with disease severity.20 In such cases, these eruptions may hold prognostic value for healthcare providers monitoring disease progression.36

Livedo Reticularis and Vascular Lesions in COVID-19

Description of Lesion

Livedo reticularis in COVID-19 patients presents as a distinctive purplish, net-like pattern on the skin, often visible on the lower limbs and occasionally extending to the trunk.37 This pattern resembles a vascular “fishnet” and can vary in intensity from faint to deep purple, depending on changes in blood flow and localized hypoxia.38 The image below is an example and is in compliance with DermNet NZ watermark image license terms.

Pathophysiology

The underlying mechanisms of livedo reticularis and vascular lesions in COVID-19 patients involve a combination of direct viral effects on endothelial cells, immune responses, and hypercoagulable states. SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2 receptors on endothelial cells, which are abundant in blood vessel linings, potentially leading to direct viral damage to the endothelium.39 This endothelial injury triggers an inflammatory cascade characterized by cytokine release, particularly IL-6 and TNF-alpha, which promotes immune cell infiltration and further damages blood vessels, creating a pro-thrombotic environment.40 The resulting endothelial dysfunction is thought to activate the complement system, leading to microthrombi formation and vascular occlusion, contributing to the livedo pattern as blood flow becomes restricted in specific areas.39 Other vascular manifestations include livedo racemosa, retiform purpura, and purpuric lesions, which reflect varying degrees of blood vessel involvement and are typically associated with a more severe COVID-19 disease course.23 These vascular lesions may evolve, with livedo reticularis sometimes progressing to purpuric or necrotic patches due to tissue ischemia caused by blocked microvessels.40

Prevalence

The prevalence of livedo reticularis and other vascular lesions in COVID-19 patients is relatively low compared to other dermatologic manifestations, with studies reporting rates between 1% and 6% in hospitalized patients.37 These lesions tend to be more common in patients with severe COVID-19, including those requiring intensive care, and are more frequently observed in older adults with pre-existing conditions such as hypertension and diabetes.23 Geographic differences also appear to influence prevalence, with some European studies reporting higher rates of vascular manifestations than studies in Asia and North America, possibly due to genetic or regional healthcare variations.38,40

Clinical Significance

Livedo reticularis and vascular lesions in COVID-19 have important clinical implications. Their presence is often indicative of severe disease progression and may correlate with a higher risk of thrombotic complications, such as deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.37,39 These lesions can serve as cutaneous markers of systemic inflammation and coagulopathy, suggesting the need for closer monitoring and, in some cases, early intervention with anticoagulant therapy to reduce thrombotic risks.23 Recognizing vascular cutaneous lesions in COVID-19 patients may also prompt further investigation for potential thrombotic events in other organs, such as the lungs, kidneys, and heart, given the systemic nature of vascular involvement in severe cases.40 Prognostically, livedo reticularis and related vascular lesions are associated with a higher likelihood of adverse outcomes, including ICU admission and mortality, particularly in older male patients with comorbidities.38,39

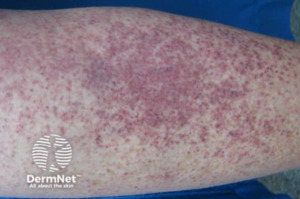

Petechiae and Purpuric Lesions in COVID-19

Description of Lesion

Petechiae and purpuric lesions in COVID-19 patients often present as small, pinpoint hemorrhages or larger, non-blanching purpuric patches resulting from subcutaneous bleeding. These lesions typically appear as reddish-purple spots that do not fade under pressure, ranging from millimeters to centimeters in size. They are primarily found on the extremities but can also appear on the trunk, face, and mucous membranes, including the oral cavity.25,41 In severe cases, purpura may evolve into ecchymoses, particularly in patients with coagulopathies or underlying hematologic conditions. In pediatric cases, these lesions are often associated with immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and may present as widespread petechiae with ecchymosis across the body, oral mucosa, and sclera.42 Petechial and purpuric lesions may precede systemic COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, and respiratory distress.43 The image below is an example and is in compliance with DermNet NZ watermark image license terms.

Pathophysiology

The development of petechiae and purpuric lesions in COVID-19 is thought to result from several interrelated mechanisms. SARS-CoV-2 can infect endothelial cells through ACE2 receptors, triggering an inflammatory response that compromises vascular integrity, leading to capillary leakage and hemorrhage.41 This endothelial damage, along with the pro-inflammatory cytokine surge characteristic of severe COVID-19, promotes platelet activation and microthrombus formation, which can obstruct capillaries and cause petechiae and purpura.43 Activation of the complement pathway and immune complex deposition in dermal blood vessels may contribute to an immune-mediated vasculitis, further damaging capillaries and exacerbating purpuric manifestations.25,42 Immune dysregulation can also lead to ITP in pediatric cases, where autoantibodies target platelets, resulting in reduced platelet counts and an increased bleeding risk.44

Prevalence

The prevalence of petechial and purpuric lesions in COVID-19 patients is relatively low, estimated to affect between 1% and 5% of hospitalized patients depending on disease severity.41,43 These lesions are more commonly reported in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19, particularly those requiring hospitalization, and are associated with an elevated risk of thrombotic complications and adverse outcomes. Geographic variations exist, with some European studies reporting a higher prevalence of vascular lesions compared to studies from Asia and North America, potentially due to differences in genetic factors, immune response, or healthcare practices.25 Pediatric cases of purpura are uncommon but are more likely to be associated with immune complications like MIS-C or severe thrombocytopenia.42

Clinical Significance

Petechial and purpuric lesions in COVID-19 patients are clinically significant, often reflecting underlying coagulopathies and heightened thrombotic risk, necessitating careful monitoring and possibly early intervention with anticoagulant therapy.41 In severe COVID-19, particularly when purpura appears alongside thrombocytopenia or DIC, these lesions may indicate disease progression and an increased risk of systemic thromboembolic events.42 For pediatric patients, widespread petechiae or purpura associated with ITP or MIS-C indicates a high bleeding risk, often requiring treatments such as corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) to manage the risk.44 Recognizing these vascular manifestations in COVID-19 patients, both adult and pediatric, may prompt further investigation into systemic coagulopathy, potentially improving outcomes through early intervention and targeted therapies.43

Treatment and Management of Dermatological Manifestations in COVID-19

The treatment and management of dermatological manifestations in COVID-19 require a tailored approach depending on the severity and type of skin involvement. General management of cutaneous lesions involves symptomatic treatment aimed at relieving discomfort and controlling inflammation. For mild cases, topical corticosteroids are often prescribed to reduce inflammation and itching, particularly for conditions such as maculopapular rashes and urticarial lesions.25,41 Antihistamines can also be used to relieve pruritus associated with urticarial rashes.43 For vesicular eruptions resembling varicella, treatment may include topical antiseptics to prevent secondary bacterial infections and calamine lotion to soothe itching.34 In cases of petechial or purpuric lesions, especially those associated with coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia, careful monitoring is essential to assess systemic involvement and bleeding risk.42 In children presenting with immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), management may involve intravenous immunoglobulin and corticosteroids to stabilize platelet counts and prevent significant bleeding complications.23,42

Severe cases of cutaneous manifestations often correlate with a pronounced inflammatory response and systemic involvement, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children or widespread vasculitis in adults.23,40 In these instances, systemic corticosteroids are commonly administered to control widespread inflammation, and systemic immunosuppressants may be considered for patients exhibiting severe immune dysregulation.40 Anticoagulant therapy is essential for managing vascular lesions like livedo reticularis or retiform purpura to reduce the risk of thrombotic complications.37,39 Management of severe cases often involves a multidisciplinary team, including dermatologists, infectious disease specialists, and hematologists, to provide comprehensive care.37

Monitoring and follow-up are crucial in managing dermatological manifestations, especially for patients with severe or persistent lesions. Regular follow-up ensures that complications, such as secondary infections or exacerbation of coagulopathies, are promptly addressed.20,44 For patients with vascular lesions and livedo reticularis, follow-up includes monitoring for signs of systemic thrombosis and progression to conditions like deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.39 Pediatric patients with conditions such as ITP require periodic platelet count assessments and monitoring for signs of recurrent bleeding.42

Patient education is an essential component of managing COVID-19-associated skin conditions. Patients should be informed about potential triggers that may exacerbate symptoms, such as certain medications and underlying autoimmune conditions, to optimize treatment and reduce recurrence.20,31 In some cases, dermatologic sequelae may persist even after recovery from COVID-19, necessitating long-term management strategies, including maintenance therapy with topical agents and monitoring for chronic skin conditions.41,44

Diagnostic Approaches to COVID-19-Associated Skin Lesions

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented numerous challenges, not only through its respiratory symptoms but also through a range of skin lesions associated with the virus. The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) has established a COVID-19 Dermatology Registry that provides a framework for classifying these cutaneous manifestations. This classification is crucial for accurate diagnosis, especially since many lesions have been identified by non-dermatologists, which can lead to misclassification and variability in reporting. Skin manifestations can generally be categorized into two groups: those caused by an immune response to the virus, such as viral exanthems, and those that arise as secondary effects of the disease, such as vasculitis and thrombotic issues. This classification aids dermatologists in diagnosing skin lesions in COVID-19 patients, facilitating a better understanding and improved treatment.45

While these dermatological conditions have distinct presentations, they often resemble lesions seen in other viral infections, making it challenging to attribute them solely to COVID-19 without further research. Therefore, understanding the respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 alongside these skin lesions is essential for clinicians to form a comprehensive diagnostic approach and improve patient outcomes. Skin lesions include maculopapular rashes, urticarial eruptions, vesicular lesions, livedo reticularis, and chilblain-like lesions, each posing unique diagnostic challenges. Dermatologists use specific laboratory and histopathological findings to identify and distinguish these lesions, supported by recent studies.

Maculopapular Rash

Maculopapular, or morbilliform, rashes are the most frequently observed skin manifestation in COVID-19, affecting an estimated 11% to 47% of dermatological cases associated with the virus.3,9 These rashes appear as widespread, symmetric red patches with raised areas, typically found on the chest, abdomen, back, arms, and legs. The onset of these rashes can vary among patients, sometimes appearing alongside respiratory symptoms or emerging later in the disease course, suggesting a temporal association with other COVID-19 symptoms. Maculopapular rashes have been correlated with more severe COVID-19 cases, with retrospective studies noting a higher hospitalization rate (45% to 80%) in COVID-19 patients with these eruptions compared to those without the rash.45

Histologically, these rashes show spongiosis (intercellular edema) and perivascular inflammatory infiltrates in the skin. Interestingly, while neutrophils and eosinophils may surround thrombosed vessels in affected areas, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein itself has not been detected in skin biopsies. This suggests that morbilliform eruptions might not be directly caused by the virus but may instead result from the body’s inflammatory response to the infection. For diagnostic purposes, PCR testing can confirm active COVID-19 infection in patients presenting with these rashes, while serological testing is useful when the rash appears after respiratory symptoms have resolved.45

Urticarial Eruptions

In COVID-19 patients, urticaria commonly presents as well-defined, red, raised, and itchy plaques, resembling hives. This type of rash, which typically results from allergenic triggers or infections, can also occur with SARS-CoV-2 infection. COVID-related urticarial eruptions involve the release of histamine from mast cells or basophils in the upper dermis, increasing vascular permeability and potentially causing angioedema. Studies have documented that urticaria accounts for 8-19% of COVID-19 skin symptoms, and although its severity can vary, it is sometimes the first or only indicator of the virus. Research presents mixed findings on the prognosis of COVID-19 patients with urticaria; some studies report higher morbidity among these patients, while others suggest a better prognosis due to eosinophilia, though the mechanism remains unclear. Dermatologists may rely on clinical evaluation of urticarial plaques, supported by PCR testing, to confirm a COVID-19 diagnosis in patients presenting with these lesions, especially if accompanied by fever.45

Vesicular Lesions

Vesicular lesions are a prominent dermatological manifestation associated with COVID-19, occurring in approximately 9-13% of patients with skin lesions. These varicella-like rashes typically develop three days after the onset of systemic COVID-19 symptoms such as fever, cough, and fatigue, although in some cases, they may precede these symptoms. Generally, these lesions resolve within eight days without scarring. Dermatologists can identify two morphological patterns of these vesicular eruptions: a diffuse pattern, characterized by varying stages of papules, vesicles, and pustules primarily affecting the trunk, and a localized pattern, where lesions appear uniformly in one area of the body, often the chest or upper abdomen. Notably, these COVID-19-related lesions tend to be non- or mildly pruritic, distinguishing them from typical varicella exanthems. Vaso-occlusive lesions linked to SARS-CoV-2 infection may result from activation of the complement system, leading to microvascular damage and vasculitis that can affect various organs, including the skin. Research indicates that these vascular manifestations are more prevalent in older adults, potentially due to factors like medication exposure, immune system dysregulation, and a higher incidence of comorbidities.3

Histological findings from affected skin show features consistent with viral exanthems, such as vacuolar degeneration and dyskeratotic cells. Despite these histological differences, the recognizable clinical presentation of vesicular eruptions can help dermatologists identify potential COVID-19 infections, supporting timely diagnosis and management of the disease.45

Livedo Reticularis

Livedo reticularis (LR) is characterized by a transient or persistent, violaceous, net-like skin discoloration resulting from physiological or pathological reductions in blood flow to the skin. According to the AAD’s Dermatology Registry, livedo reticularis accounted for 5.3% of confirmed COVID-19 cases with cutaneous manifestations. Histologic findings of livedo reticularis in a patient with confirmed COVID-19 revealed pauci-inflammatory thrombotic vasculopathy. However, most reported cases of livedo reticularis in COVID-19 patients have been mild, transient, and without thromboembolic complications.

Reports on the treatment of LR in COVID-19 patients are limited. One case study described a patient who developed LR on the trunk and bilateral proximal upper extremities following COVID-19 infection, with symptoms resolving after treatment with acetaminophen, heparin, hydroxychloroquine, and oxygen. In contrast, other cases of COVID-19-related LR have resolved spontaneously.

Identifying specific rash morphologies, including livedo reticularis, is critical due to their association with increased disease severity and the likelihood of requiring intensive care. Research indicates a strong correlation between certain skin manifestations and a higher risk of serious outcomes, including ICU admission. For instance, in a systematic review, patients exhibiting livedo reticularis showed a significantly elevated odds ratio of 10.71 for ICU transfer. This underscores the importance of dermatological assessments in COVID-19 management, as early identification of these rashes can facilitate rapid clinical decision-making and resource allocation in hospital settings.46

Chilblain-like Lesions (COVID Toes)

Chilblain-like lesions (CLL), often referred to as “COVID toes,” are now a recognized marker of COVID-19, notable for their unique presentation and suspected association with SARS-CoV-2. These lesions typically appear as violaceous or erythematous plaques, often accompanied by swelling, primarily affecting the fingers and toes. Unlike traditional chilblains, which are rare and usually triggered by cold exposure, COVID-related CLL can appear without such triggers, suggesting a possible immune response to the virus. Studies report that CLL represents 19% to 38% of COVID-related skin manifestations. The condition shows a slight female predominance, with a mean age of onset around 25 years, and most cases present without additional systemic symptoms.47 However, in a systematic review, CLL was identified as the most common skin manifestation, accounting for 54.2% of cases and particularly prevalent in younger individuals with a mean age of 21.5 years.48 These lesions were associated with milder disease and a significantly lower need for hospitalization (odds ratio [OR] 35.36). This discrepancy in data could be due to increased awareness of these lesions, amplified by media coverage, leading to higher reported rates. COVID-19 testing is frequently negative, suggesting that CLL may occur independently of active viral infection. Histologically, CLL often shows lymphocytic inflammation surrounding blood vessels and sweat glands; in some cases, SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins have been detected within endothelial cells, hinting at direct viral effects on the vasculature.45

Although mostly benign, CLL may take two to eight weeks to resolve and, in some cases, can persist for months. These findings highlight the diagnostic value of CLL in COVID-19, especially for detecting possible asymptomatic infections in younger female patients. Histopathological examinations have revealed distinct features associated with COVID-19, including superficial and deep perivascular infiltrates of lymphocytes or neutrophils, epidermal alterations such as apoptotic and necrotic keratinocytes, and thrombotic vasculopathy in dermal vessels. Notably, skin biopsies often show evidence of endothelial cell injury and necrosis of sweat glands.2

Imaging procedures, particularly CT scans, exhibit high sensitivity for diagnosing COVID-19 and are essential for assessing lung involvement and disease progression, although they may miss early lung abnormalities as skin manifestations can precede respiratory symptoms. Common findings include bilateral patchy shadowing, although some patients may have normal CT scans. Alongside imaging, notable laboratory findings include elevated CRP levels, thrombocytopenia, and increased D-dimer, which correlate with disease severity and skin involvement. One study reported elevated CRP in 92.14% of COVID-19 patients, while thrombocytopenia was observed in 20.7% of cases, underscoring the importance of these tests in evaluating disease impact.2

Differential Diagnosis

When evaluating cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19, it is essential to consider a broad differential diagnosis, as various skin conditions can present similarly. Viral exanthems, such as those seen in measles and rubella, may mimic morbilliform eruptions and are characterized by generalized, symmetric rashes often accompanied by distinct systemic symptoms specific to each virus. In contrast, psychophysiological dermatoses, including chronic urticaria and psoriasis, can be exacerbated by psychological stress and may also present with similar skin findings.45 Primary cutaneous psychopathology can lead to skin lesions stemming from underlying psychiatric conditions, such as delusional infestations or factitious disorders, where patients inflict harm on themselves. Additionally, cutaneous sensory disorders, characterized by abnormal sensations like burning or itching, can complicate the clinical picture and may overlap with dermatological symptoms observed in viral infections.45

In SARS-CoV-2-positive patients, it is vital to consider possible drug-related reactions, which can manifest as immediate or delayed hypersensitivity responses characterized by immune cell activation, including eosinophilia and mast cell activation.47 Severe cases, such as DRESS (Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms), may lead to systemic symptoms like lymphadenopathy and facial swelling. Medications like hydroxychloroquine and corticosteroids are also associated with cutaneous manifestations, including acneiform rashes, telangiectasias, and various forms of dermatitis. Furthermore, disfiguring dermatoses contributing to psychosocial comorbidities, such as alopecia areata and telogen effluvium, can lead to visible changes that affect patients’ mental health, similar to the emotional distress caused by morbilliform eruptions or other rashes seen in COVID-19.45

Dermatological conditions have also emerged among healthcare workers due to prolonged use of personal protective equipment (PPE) during the pandemic, which must be differentiated from COVID-19-associated skin lesions. These conditions include acne, likely exacerbated by heat and humidity; periorificial dermatitis, presenting as inflammatory papules around the eyes, nose, and mouth; and papulopustular rosacea, which features facial erythema with telangiectasias. Other notable conditions are pressure injuries causing skin and soft tissue damage, irritant contact dermatitis, and allergic contact dermatitis arising from materials in PPE, leading to localized inflammation. Hand eczema manifests as itchiness, dryness, and redness due to excessive hand washing and glove use, while seborrheic dermatitis, often worsened by the microenvironment of face masks, affects areas like the scalp and nasolabial folds. Although hand hygiene-related dermatitis is generally a concern for healthcare workers, excessive hand hygiene may also lead to hand eczema in the general population.48

These lesions can be distinguished from COVID-19-associated skin manifestations through serological testing, particularly when identifiable causes for the rashes are not apparent, as this helps confirm or rule out SARS-CoV-2 infection and tailor treatment strategies accordingly.48

Discussion

This systematic review highlights the clinical importance of recognizing dermatologic manifestations in COVID-19 as potential early indicators of infection, particularly in patients without respiratory symptoms. Certain cutaneous signs, including angioedema and chilblain-like lesions, frequently appear before other symptoms, aiding in the early diagnosis of COVID-19.5 For example, angioedema has been reported to precede respiratory symptoms by 2-11 days, often presenting on the face and trunk.5 In one case, a patient with a history of ACE inhibitor use developed angioedema, suggesting that COVID-19 may trigger this condition in at-risk patients, particularly those taking ACE inhibitors.49 These findings indicate that dermatologic signs may be valuable for early COVID-19 detection, potentially helping to control virus transmission through timely diagnosis and isolation.

Chilblain-like lesions, also known as “COVID toes,” have been widely reported as early indicators, especially in children and young adults.6 These lesions manifest as red-to-violet papules on the toes and fingers, often following upper respiratory symptoms by one to two weeks and presenting with itching, pain, or burning.50 Notably, approximately 10% of patients with COVID-19-associated skin lesions exhibited no other symptoms, underscoring the potential utility of dermatologic signs in identifying otherwise asymptomatic cases.7 When chilblain-like lesions appear later in the disease course, they frequently coincide with PCR-negative results, which may suggest an immune response rather than active viral infection.6

Future research should investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying COVID-19-related skin involvement. SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2 receptors, which are present in keratinocytes of the skin and oral mucosa, potentially facilitating local viral entry. However, systemic immune responses likely play a substantial role as well.51 Type I interferons (IFNs), released by dendritic cells in the skin, may initiate inflammatory cytokine release, potentially exacerbating autoimmune or other pre-existing dermatologic conditions.8 Alopecia areata, for instance, has been frequently reported in COVID-19 patients and may result from either antigen mimicry or heightened T-cell activity, attacking hair follicles through increased MHC-I expression.8 Such mechanisms could explain why certain COVID-19-related dermatologic symptoms persist beyond acute infection.

In elderly COVID-19 patients, vascular-type skin lesions such as retiform purpura, necrotic or ischemic changes, and livedo reticularis are associated with severe outcomes and increased mortality.52 These vascular lesions likely result from SARS-CoV-2-induced endothelial damage and hypercoagulability, leading to microthrombi formation.52 This hypercoagulable state, along with elevated ACE2 receptor expression in elderly skin, may contribute to these severe manifestations, potentially serving as prognostic indicators in older patients. Conversely, the second most common dermatologic presentation in individuals aged 65 or older is a maculopapular rash, which is associated with a milder COVID-19 disease course.52

The review acknowledges several limitations in the studies reviewed. Many studies had small sample sizes, lacked follow-up, and exhibited geographic variability, which may affect the generalizability of findings.5 Additionally, some studies relied on clinical observation without PCR confirmation, especially in cases with delayed dermatologic presentation.51 The limited follow-up also restricts insight into the long-term impact of COVID-19-associated skin lesions. These limitations emphasize the need for large, multi-center studies to clarify the clinical significance, timing, and prognostic value of dermatologic manifestations in COVID-19, ultimately supporting their use as diagnostic and prognostic tools in managing the disease.

Conclusion

The wide range of dermatological manifestations associated with COVID-19 highlights the importance of recognizing these symptoms as potential indicators of infection. These skin manifestations—such as COVID-19 toes, maculopapular rashes, urticarial lesions, vesicular eruptions, and vascular lesions—often precede or accompany systemic symptoms, providing early diagnostic clues for clinicians. Awareness of these cutaneous signs can aid in the prompt diagnosis of COVID-19, particularly in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic individuals, facilitating timely intervention and reducing transmission risks.

Moreover, the inclusion of dermatologists in interdisciplinary COVID-19 care teams can enhance patient outcomes, as they are equipped to identify, differentiate, and manage these dermatological manifestations. Dermatologists’ involvement is especially relevant for severe cases where cutaneous signs may indicate underlying systemic complications, such as coagulopathies or cytokine storms. These insights underscore the need for a comprehensive approach to COVID-19 that considers skin symptoms not only as potential diagnostic markers but also as vital components of effective management and prognosis